We like to describe Ryedale Folk Museum as a treasure trove of heritage objects and stories. But fifty years ago a tale involving real treasure was unfolding within our largest building. Witihin the medieval Manor House known as Harome Hall, a mysterious spoon was discovered in the thatch.

As with other buildings at the Museum, such as Stang End, Harome Hall is of cruck-frame construction. These were popular in Ryedale and the North York Moors, but particularly in the villages of Harome and nearby Pockley. It is likely that the Hall was the highest status of all the cruck buildings in the region, with its vast crucks rising to the ceiling to create an elaborate display.

The grand crucks at Harome Hall in 1971

During feudal times, except for the village church, a manor house was generally the most important building in the area. Archaeological evidence shows that the site in Harome had hosted an important dwelling for eight hundred years.

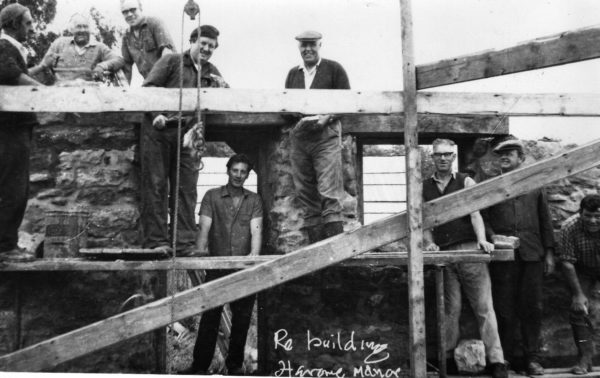

However, by the 1970s things looked a little different. The hall was described by Museum volunteers as ‘crumbling’. The thatch was rotten thatch and the roof collapsing. A rescue plan was put in place. One of the Museum’s early trustees, Bill Goodall, organised for Harome Hall should be removed to the Museum where it would be rebuilt in its ‘original simplicity’.

Harome Hall being rebuilt at the Museum in 1971, by Geoffrey Willey

It was a physically-demanding process. Curator Bert Frank set about relocating the building with his team of over a dozen dedicated volunteers. It was volunteer Robin Butler who found the spoon whilst dismantling the building on January 17, 1971. It was tucked away within the thatched roof.

Initially, the spoon seemed to be quite insignificant. According to Bert’s diary it “aroused little interest at the time” and lay for some days in the Finds’ Tray, along with various pieces of pottery. It was assumed to be made of tin or pewter.

It’s not entirely surprising that the spoon was not a priority that week. Various accounts recall the difficult working conditions in the Manor House. Occasionally a cry of “Timber!” would ring out as a roof beam crashed to the floor nearby.

In total, 14 volunteers worked to relocate Harome Hall to Ryedale Folk Museum. Photo by Raymond Hayes.

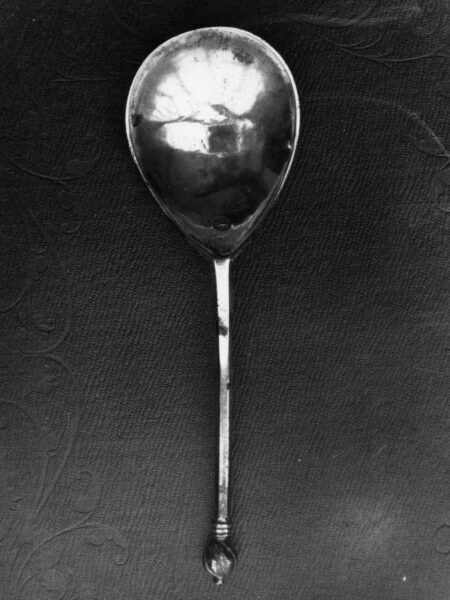

However, when Bert began to clean the piece, he revealed a silver hallmark. The spoon was a significant find. It was now also a candidate for ‘treasure trove’. This is the label applied when a hidden item of treasure is too old for the heirs to be traced. In fact, the spoon is now known to have been made in 1510.

It is a beautiful piece, measuring approximately fifteen centimetres in length. It has a shallow, fig-shaped bowl in keeping with its intended use for general eating, rather than for liquids as we might use a spoon today. This bowl tapers into a hexagonal stem, ending with a finial knop.

The Silver Spoon. It is now in the British Museum.

Most of us are familiar with the symbolic value of a silver spoon, which stems from the monetary value of this particular item. The expression to be ‘born with a silver spoon in one’s mouth’ is associated with inherited wealth and may also refer to the fact that silver spoons were sometimes christening presents.

Before established place settings at dinner tables, spoons functioned in place of a range of utensils. They were often carried in pockets, sometimes in a leather case, for use as needed. Producing a silver spoon would have been an indicator of social status, particularly if those about you were using more common wooden spoons. Unsurprisingly, they were also mentioned in wills.

The spoon found in our Manor House was believed to have been hidden, not lost. It is very likely that whoever concealed it within the thatch spent many hours fruitlessly searching later. The discovery raised fascinating, and sadly unanswered, questions about the set of circumstances that led to an item of such value being hidden.

One theory relates to the English Civil War, during which Helmsley Castle was besieged in 1644 by Sir Thomas Fairfax. The Royalists held on for three months before surrendering. It is possible that the spoon was concealed at that time by the Hall’s inhabitant, the widowed Mary Morrett, to prevent it being stolen by Oliver Cromwell’s ‘Roundheads’, led by Sir Fairfax. They would have been frequent visitors to the villages surrounding Helmsley in search of supplies during the siege.

You can explore Harome Hall, one of over 20 heritage buildings at the Museum, as part of your family day out on the North York Moors.

The Manor House, Harome Hall, at Ryedale Folk Museum by Angela Waites

Listen to Robin Butler talk about finding the silver spoon: