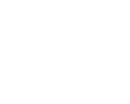

If the word ‘shepherdess’ calls to mind the image of nursery-rhyme character ‘Little Bow Peep’, the historic moorland figure of Rose Farrow will come as a surprise. Rose was Hutton-le-Hole shepherdess for several decades during the middle of the twentieth century and of our collection photographs at Ryedale Folk Museum actually show her on horseback. This mode of travel would have been necessary due to the size of the terrain!

Rose shepherding on horseback

Rose is often pictured with her faithful sheepdog Fly. Tending sheep on the North York Moors was a gruelling and effortful task, especially in winter. Incredibly, Rose continued to work until her eighties, helped by her nephew, Jeffrey Featherstone, and her brother, Charles. By the mid-1960s, she was looking after approximately four hundred sheep.

Rose had taken over the role from her father who had been able to form a flock thanks to donations of moorland grazing rights from the other villagers of Hutton-le-Hole. He is known to have consolidated them into one large flock during the 1880s.

Traditional moorland farming

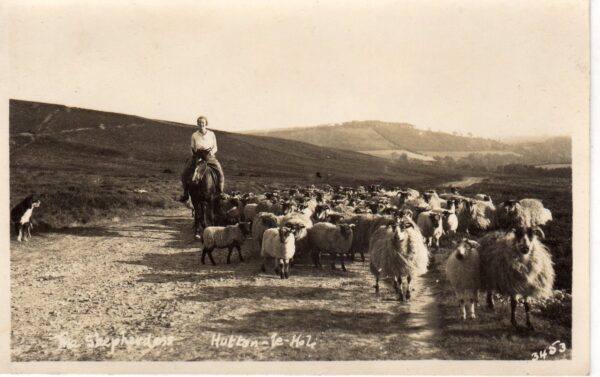

On the moors, sheep are ‘heafed’ in a process known as heft farming. This means that the sheep do not need to be restrained by physical boundaries such as fences or walls. Instead, they come to stay in one particular area of land. This traditional method of grazing has been in practice for hundreds of years, supported by knowledgeable farmers, shepherds and shepherdesses. Heft farming would require great vigilance and constant shepherding at the start, until a flock learnt the required behaviour and stayed in their place, ideally passing this knowledge from ewes to their lambs.

Rose with her flock

Like the majority of moorland flocks, those shepherded by Rose were Blackface sheep. Rose was recognised for her expertise at breeding and was a member of the Scottish Blackface Sheep Society. This breed is well-suited to the heather of the North York Moors and known for having a robust constitution to survive the rigours of moorland life. Sadly, they are also at risk of death and injury in these parts from vehicle collisions.

Though the work kept Rose occupied continually, there were also times of particularly intensive activity within the calendar, for example lambing season. Ewes often need careful supervision during the birth at a time when swift intervention can mean the difference between life and death. There are local stories of Rose riding out bareback in an emergency, not even stopping to saddle up, in order to save time.

Rose and the community

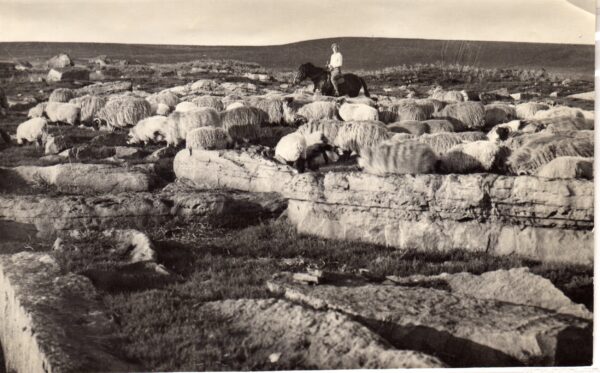

Rose lived her entire life in Hutton-le-Hole in the aptly-named ‘Rose Cottage’, from her birth in 1911 until her death at the age of 97. It was a time when village life was led around the seasons and celebrations. In this village, she was a Sunday School teacher for thirty-six years, served on the Village Hall Committee and was involved in the organisation of the Mell Supper every year. Many farming tasks were also communal. Traditionally, dipping was an important process designed to eliminate parasites from the sheep’s bodies, including ticks, lice and blowfly. Large gatherings for ‘clipping’ were also looked forward to, with customary clipping day foods consumed, including special cheesecake with a layer of butter.

Rose dipping sheep

In 2008, Jeffrey, who had been caring for Rose until her death, donated a number of her personal items to the Museum. We see a fascinating insight into a remarkable life of moorland farming through her objects, including her pitchfork, branding iron, razor strop (for sharpening shearing equipment) and metal suckling restraint.

A particularly prized item, synonymous with the profession, is Rose’s shepherdess crook. Made from hazel wood with a horn handle and ornate carved thistle design, this crook is clearly a beautiful decorative item, not intended for use.

You can watch a short British Pathe film about Rose Farrow, made in 1965.